Prospectus: Collaborative Explorations

Table of Contents

- This course is a gift—the chance to be open—open-ended in design, open to process, open to other perspectives, open to changing your ideas, and open to sharing. Of course this means it’s risky too—you won’t always know when you’re coming from or where you are going—you might think you aren’t sufficiently grounded by the course. But you have the freedom to change that—and being on the other side of it now, I see it works out beautifully. The attention to process provides you the tools to grow and by the end you’re riding the wave of your earlier work...

This prospectus combines practical information about how online CEs run with ideas and questions about how to make sense of what happens in them. Links are provided to further details. A portal, files/CE.html, provides a short overview and information about upcoming CEs.

Overview and contrast to connectivist MOOCs

The tangible goal of any CE is to develop contributions to the topic defined by the case, which is written by the host or originator of the CE to be broad and thought-provoking (see examples below). An experiential goal is to be impressed at how much can be learned with a small commitment of time using the CE structure to motivate and connect participants.The standard model for an online CE is to have four sessions spaced one week apart, in which the same small group interacts in real time live via the internet for an hour. Participants spend at least 90 minutes between sessions on self-directed inquiry on the case, sharing of inquiries-in-progress with their small group and the wider community for the CE, and reflecting on the process—reflection that typically involves shifts in participants' definition of what they want to find out and how. Any participants wondering how to define a meaningful and useful line of inquiry is encouraged to review the scenario for the CE, any associated materials, posts from other participants, and think about what they would like to learn more about or dig deeper into. Everyone is left, in the end, to judge for themselves whether what interests them is meaningful and useful. During the live sessions, CE participants can expect to do a) a lot of listening to others, starting off in the first session with autobiographical stories that make it easier to trust and take risks with whoever has joined that CE and b) writing to gather their thoughts, sometimes privately, sometimes shared.

There is no assumption that participants will pursue the case beyond the limited duration of the CE. This said, the tools and processes used in CEs for inquiry, dialogue, reflection, and collaboration are designed to be readily learned by participants so they can translate them into their own settings to support the inquiries of others. In short, online CEs are moderate-sized open online collaborative learning. It remains to be seen whether CEs will attract enough participants to scale up to multiple learning communities around any given CE scenario, each hosted by a different person and running independently.

A MOOC (massive open online course) seeks to get masses of people registered, knowing that a tiny fraction will complete it, while a CE focuses on establishing effective learning in small online communities then potentially scale up from there. A course is not the default model for teaching/learning in CEs. Instead, CEs aim to address the needs of online learners who want to:

- dig deeper, make “thicker” connections with other learners

- connect topics with their own interests

- participate for shorter periods than a semester-long MOOC

- learn without needing credits or badges for MOOC completion.

High-profile MOOCs do not, it would be fair to say, appear to be conducive of deep or thick inquiry. Sharing of links can be active in connectivist or c-MOOCs, but annotation of those links is not common. CE live sessions and posts, however, generally take the form of participants’ thoughtful reflections and syntheses. While MOOCs do succeed in connecting with participants from a distance, they are not governed by what has been learned about online learning—or learning more generally. The use of the internet for CEs, in contrast, is guided by two principles of online education (Taylor 2002):

- Use computers first and foremost to teach or learn things that are difficult to teach or learn with pedagogical approaches that are not based on computers (e.g., bring in participants from a distance; make rapid connections with informants or discussants outside the course; contribute to evolving guides to materials and resources).

- Model computer use on best practices for teaching-learning without computers (e.g., students [or participants] become self-directed and collaborative learners—gaining tools, ideas, and support from instructors and peers [or other participants] who they can trust; integrating what they learn with their own personal, pedagogical, and professional development.

Examples of scenarios or cases

Connectivist MOOCs: Learning and collaboration, possibilities and limitations- The core faculty member of [a graduate program] at... urban public university want help as they decide how to contribute to efforts at [the university] to promote open digital education... It is already clear that [their] emphasis will not be on x-MOOCs, i.e., those designed for transmission of established knowledge, but on c-MOOCs. "c" here stands for "connectivist" in recognition of the learning that takes place through horizontal connections and sharing made within communities that emerge around, but extend well beyond, the materials provided by the MOOC hosts (Morrison 2013; Taylor 2013). What [the Program] is not so clear about yet is the kinds (plural) of learning that are happening in cMOOCs. What are their possibilities and limitations? Ditto for kinds of creativity, community, collaboration, and openness. By "limitations" [the Program] is especially interested in anticipating undesired consequences...

Science and policy that would improve responses to extreme climatic events

- ...Recent and historical cases of climatic-related events shed light on the impact of different emergency plans, investment in infrastructure and its maintenance, and reconstruction schemes. Policymakers, from the local level up, can learn from the experiences of others and prepare for future crises... The question for this case is how to get political authorities and political groups—which might be anywhere from the town level to the international, from the elected to the voluntary—interested in learning about how best to respond to extreme climatic events and pushing for changes in policy, budgets, organization, and so on. It should even be possible to engage people who resist the idea of human-induced climate change—after all, whatever its specific cause, extreme climatic events have to be dealt with....

Further examples can be viewed at files/CEt.

Mechanics and processes

In a small group running for a delimited period, a private google+ community or its equivalent suffices for participants to follow discussion threads. A google+ hangout allows a group of 10 to meet and share any visual aids. Use of such technology is simple, widely accessible, and unencumbered by concerns about production values and costs.The sequence of the CE sessions is detailed at files/CEs, but, in brief:

- Before the first live session: Participants review the scenario, the expectations and mechanics, join the google+ community and get set up technically for the hangouts.

- Session 1: Participants getting to know each other. After freewriting to clarify thoughts and hopes, followed by a quick check-in, participants take 5 minutes each to tell the story of how they came to be a person who would be interested to participate in a CE on the scenario. Other participants note connections with the speaker and possible ways to extend their interests, sharing these using an online form.

- Between-session work: Spend at least 90 minutes on inquiries related to the case, posting about this to google+ community for the CE, and reviewing the posts of others.

- Session 2: Clarify thinking and inquiries. Freewriting on one’s thoughts about the case, followed by a check-in, then turn-taking “dialogue process” to clarify what participants are thinking about their inquiries into the case. Session finishes with gathering and sharing thoughts using an online form.

- Between-session work: Spend at least 90 minutes a) on inquiries related to the case and b) preparing a work-in-progress presentation.

- Session 3: Work-in-progress presentations. 5 minutes for each participant, with “plus-delta” feedback given by everyone on each presentation.

- Between-session work: Digest the feedback on one’s presentation and revise it into a self-standing product (i.e., one understandable without spoken narration).

- Session 4: Taking Stock. Use same format as for session 2 to explore participants’ thinking about a) how the CE contributed to the topic (the tangible goal) and to the experiential goal, as well as b) how to extend what has emerged during the CE.

- After session 4 (optional): Participants share on a public google+ community not only the products they have prepared but also reflections on the CE process.

Ideas and questions about how to make sense of what happens in CEs

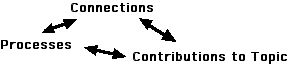

Re-engagement with oneself as an avid learner and inquirer in CEs or PBL is made possible by the combination, shown in Figure 1, of:

- the tools and processes used for inquiry, dialogue, reflection, and collaboration;

- the connections made among the diverse participants who bring diverse interests, skills, knowledge, experience, and aspirations to the CE/PBL case; and

- the participants' contributions to the topics laid out in the scenarios from which each CE/PBL case begins.

Figure 1. Triad of aspects of a CE or PBL

The re-engagement, in turn, makes it more likely—or, at least, so is the hope—that participants carry this triad over into subsequent changes in:

- their own inquiries and teaching-learning interactions for life-long learning;

- the ways that they support inquiries of others;

- other practices of critical intellectual exchange and cooperation; and

- challenging the barriers to learning often associated with expertise, location, time, gender, race, class, or age.

In thinking about how CEs can provide opportunities for participants to re-engage with themselves as avid learners and inquirers, inspiration has been drawn from a number of sources:

- Students in science-in-society graduate courses that use PBL:

- "This course provides a structure for me to learn about what really interests me." (See also the quote at the start.)

- The “4Rs” framework based on the experience of the New England Workshop on Science and Social Change:

- Build Respect for each others’ diversity and our own diverse strands, which make it more likely for little Risks in which participants in the activities stretch beyond the customary and for little Revelations to affirm these Risks. The steady experience of these Revelations or insights leads to Re-engagement in the realms of our customary work (Taylor 2012, p. 251ff).

- Vivian Paley’s writing about play, story-telling, and kindness among young school-children.

- In The Girl with the Brown Crayon (p. 47), Paley says to her assistant Nisha: “Isn’t it a great feeling tying together all these stories?” Nisha: “Yes, but it doesn’t feel as if I’m tying things up. No, it’s more like opening up, or maybe even discovering things I’ve forgotten.”

- In The Boy on the Beach (p. 24), Paley writes, paraphrasing a 1924 essay by V. Woolf: “[T]he teacher must get in touch with the children by putting before them something they recognize, which therefore stimulates their imaginations and makes them willing to cooperate in the business of intimacy.” (To translate this into CEs: replace “children” by “participants” and read “intimacy” as exposing vulnerabilities, aspirations, unformed ideas to each other.)

- In the same book, a colleague writing to Paley remarks (p. 25): “When [children] solve one problem, they create another to act on. By proving they are necessary and useful in a story, they demonstrate that they have a reason to exist, to be here with others.”

- Michael White’s narrative practice in family therapy and community work:

- “It is one thing to know that people are not passive recipients of life forces. But it is another thing to identify [people's multiplicity of] initiatives, and to contribute to a context that is favorable to their endurance…. [I]t is another thing to identify initiatives that might provide a point of entry to the sort of rich story development that brings with it more positive identity conclusions and new options for action in the world” (White 2011, p. 29).

- Taylor and Szteiter's Taking Yourself Seriously--"a fieldbook of tools and processes to help readers in all fields develop as researchers, writers, and agents of change."

Possible extensions

There are many possible extensions of online CEs, which were piloted in 2011 and have run most months since April 2013. Some participants might:- share the products of the CE with wider online communities

- take initiative to combine reports into drafts for publication (with all contributors as co-authors or giving permission for use of their report)

- form a group that pursues the case beyond the limited duration of the CE

- return for more CE experiences

- spread the word to others to join in subsequent CEs

- become mentors for new participants

- attend training sessions so interested participants can then host on their own or apprentice to someone else (aided by a script, files/CEscript)

- contribute to a CE collection of tools and processes to be used in shaping directions of inquiry and developing skills as investigators

- write cases for possible future CEs

- develop incentives (certificates of attainment, badges,...)

- arrange a partnership with a university to receive credits after submitting a portfolio from participation in, say, four CEs

- elicit discussion about the operations—who gets to decide what CEs get launched and when, who can host a small group, etc.

- promote "inverted pedagogy”—the idea that the experience of CEs and PBL can motivate people to identify and pursue the disciplinary learning and disciplined inquiry they need to achieve the competency and impact they desire. (This approach inverts the conventional curriculum in which command of fundamentals is a prerequisite for application of learning to real cases.)

- promote CEs as a model for MOOCs beyond large centralized providers and which a positive effect for learner populations

- undertake exploratory research, interviewing participants to develop vocabulary and themes that help articulate the effect for learners of a MOOC model that does not involve large centralized providers (e.g., http://wp.me/p1gwfa-xe)

- articulate and publish on the institutional, pedagogical, learning design, technological, and business model involved in CEs

- adapt CEs into variants that allow asynchronous small-group participation

- adapt CE wording and cases so they are accessible and attractive to participants who are less academic

- clarify the possibilities and limits of CEs with regard to accommodating participants having different levels of preparation in the topics and/or the processes of interaction

- compare and contrast CEs with the tinkering and making emphases others give to learning in ways that are social, playful, disruptive of preformed ideas of one's capabilities, and more

- organize CEs with scenarios related to a unit in a course (or to issues that arise during a connectivist MOOC) with the CE inquiries and exchanges forming additional resources for the course (or for MOOC participants)

- translate their experience into running their own PBL-style units or entire courses in format educational settings

- develop a macro to automate the process of forming communities based on registration information (currently submitted via http://bit.ly/CEApply).

- discuss the connection or disconnect between overcoming barriers to learning and overcoming barriers to who can contribute to the production of established knowledge in various fields.

References

Morrison, D. (2013). “A tale of two MOOCs @ Coursera: Divided by pedagogy,” http://bit.ly/164uqkJ (viewed 17 Nov. 2103).Paley, V. G. (1997). The Girl with the Brown Crayon. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press.

------ (2010). The Boy on the Beach: Building Community by Play. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Taylor, P. J. (2007) "Guidelines for ensuring that educational technologies are used only when there is significant pedagogical benefit," International Journal of Arts and Sciences, 2 (1): 26-29, 2007 (adapted from http://bit.ly/etguide).

------ (2013). “Supporting change in creative learning,” http://wp.me/p1gwfa-vv (viewed 17 Nov. 2103).

------ and J. Szteiter (2012). Taking Yourself Seriously: Processes of Research and Engagement Arlington, MA, The Pumping Station.

White, M. (2011). Narrative Practice: Continuing the Conversation. New York, Norton.