PLATFORM GROWING

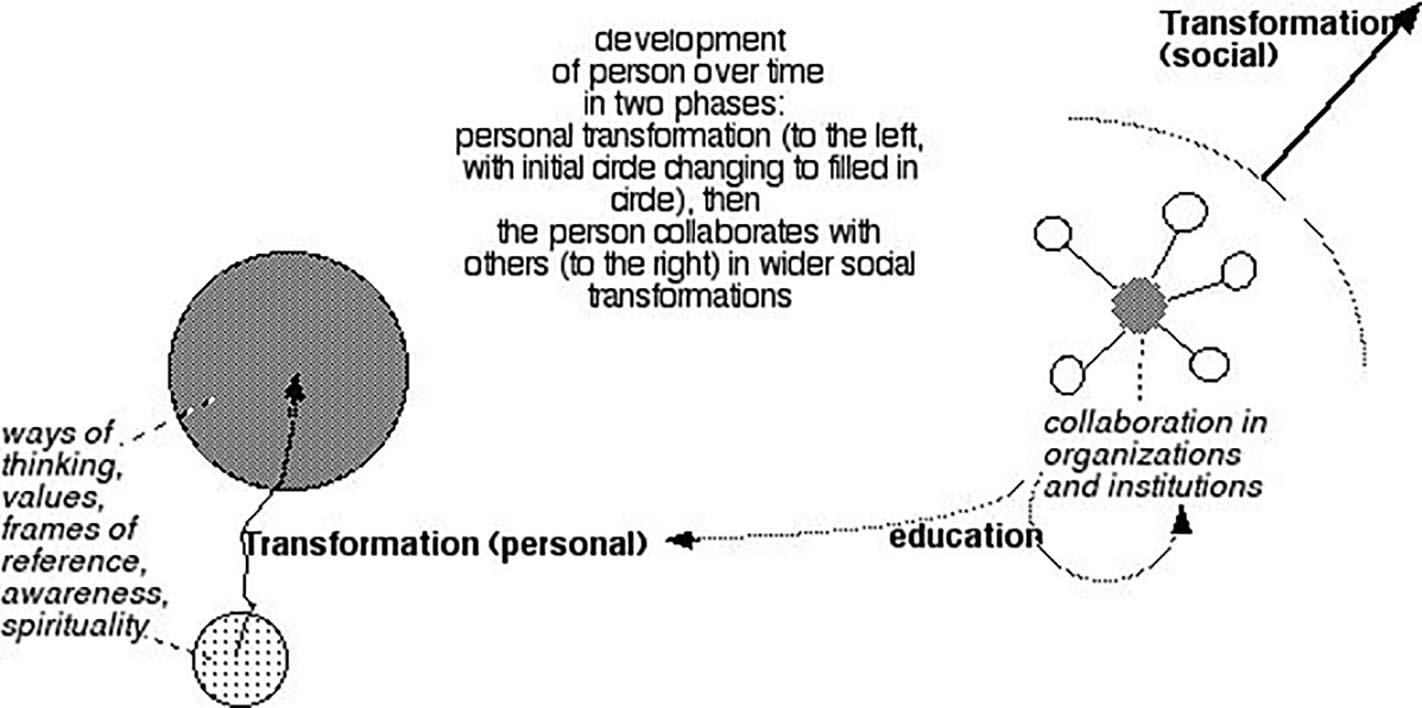

This final think-piece derives from blogposts Peter wrote, starting in 2013 while preparing a proposal for a doctoral program in the area of Transformative Learning or Education.* Whereas other programs focused on personal and social transformation, it seemed important to pay attention to fostering what we might call the platforms that support our lifelong development. (*Alas, this did not come to fruition.)A connection between personal transformation and social change has characterized transformative learning since Mezirow’s original 1978 formulation of this approach to adult education. This connection is, as schematized below, that beliefs, values, ways of thinking, assumptions, frames of reference, or self-awareness are called into question and transformed; the resulting, more critical and inclusive perspectives at the personal level are then applied to promote wider change through education, institutions, policy, and social movements.

Transformational learning emphasizes students changing beliefs, values, etc. and on this basis influencing justice in society. Education fosters personal transformation and organizational change.

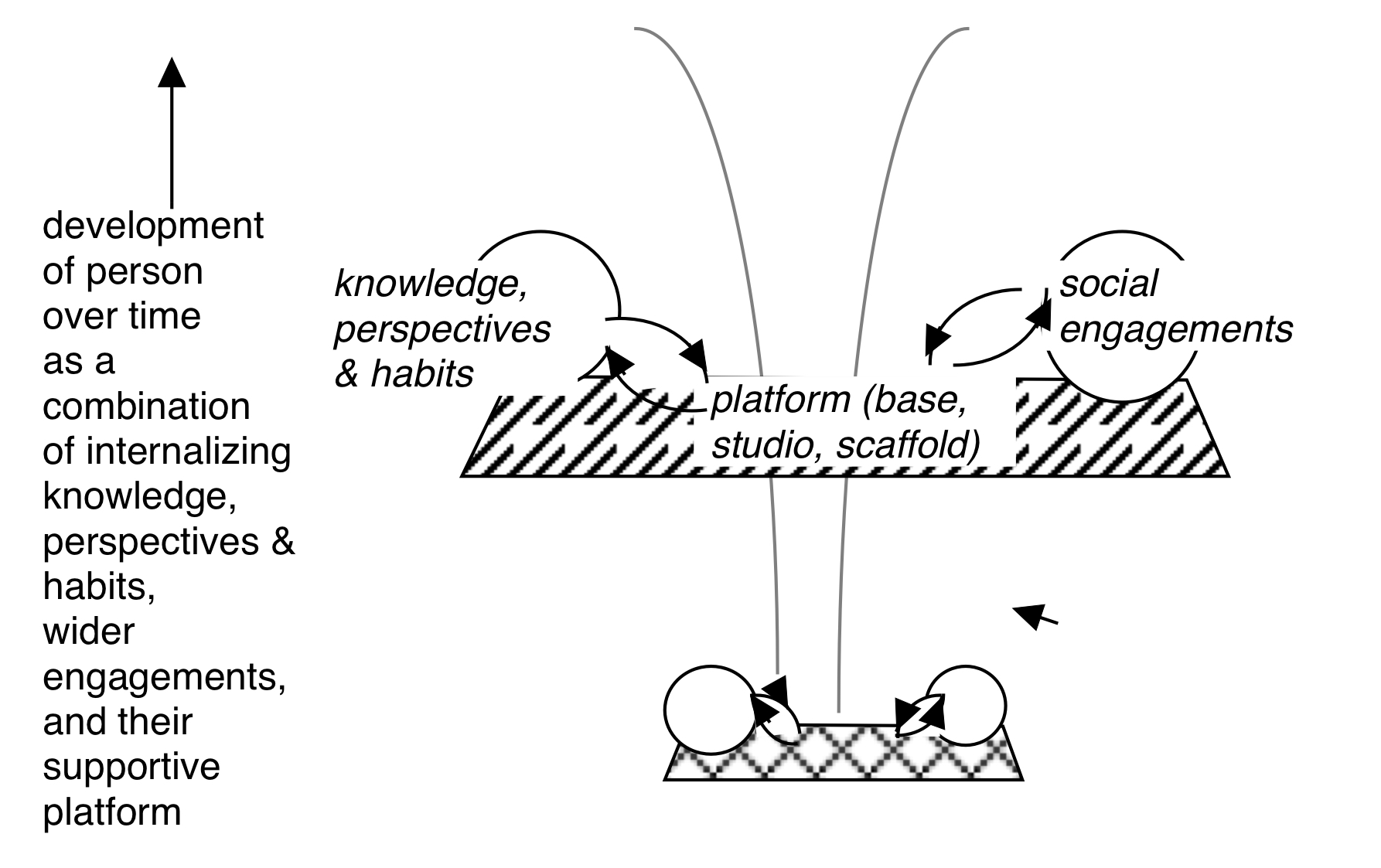

In my view, an additional level, between the personal and social, needs to be emphasized—that of well-organized, sustainable spaces in which learning, projects, collaboration, and reflection on wider engagements are fostered. Such spaces provide support for our lifelong development. Platform seems an apt term—a platform is something you can stand upon, something that supports you. It is also something beyond what is inside you—beyond your personality, willpower, drive, or creativity. The platform is the central piece of this schema below.

Transformative Education that emphasizes lifelong growing of a platform to support inquiry and engagement.

The cycling arrows to the left denotes learning new knowledge, perspectives, practices, which are more likely to stick—to be remembered, become part of your own cognitive structures or physical capabilities, become part of your own thinking and habits—if practiced in a supportive space before being put into practice in the wider world. The supportive space is one in which the teacher, coach, or colleague introduces you to new knowledge, perspectives, or practices and encourages you to take yourself seriously in the sense of putting them into practice in the wider world.

The cycle to the right is bringing your thinking and habits into engagements in the wider world, then taking stock. You are more likely to learn from what happens if you have time, space, and support to do that evaluation, reflection, and revision of plans for future engagements. The supportive space is one in which the teacher, coach, or colleague encourages you to take yourself seriously in the sense of building a constituency to keep putting your ideas and plans into practice in the wider world.

When you are developing personally and professionally through the left and right cycles, you are also improving, extending, or expanding—growing—the platform that supports your ongoing development (as depicted by the opening out lines above the platform). Conversely, if the platform is small or shaky, then your development from the two cycles and expansion of the platform might be limited.

What concretely is a platform? The prime example would be a studio, in a variety of senses:

Platform growing would also happen through making Plans for Practice—how you are going to put into practice the tools, processes, and knowledge you have been learning. And how and with whom you are going to practice putting these into practice. Platform growing could include simply keeping a journal or having a notebook with you. Indeed, platform growing would happen through using just about any of the tools and processes assembled in this book or, in short, through taking yourself seriously.

Platform growing

As children, we are highly dependent on others for our cognitive and physical development, indeed for our very sense that we are a self that develops. Here my thinking–and the schema above–is influenced by Hendriks-Jansen (1996; see Taylor 2015) and Bowlby, a psychologist who focused on the long term effects of different patterns of attachment of infants and young children to their mothers (Bowlby 1988). Bowlby and others observed what they interpreted as secure versus anxious attachment of young children to caregivers. In a situation of secure attachment the caregiver, usually the mother, is, in the child’s early years, “readily available, sensitive to her child’s signals, and lovingly responsive when [the child] seeks protection and/or comfort and/or assistance” (Bowlby 1988, 167). The child more boldly explores the world, confident that support when needed will be available from others. They have a secure base. Anxious attachment, on the other hand, corresponds to inconsistency in, or lack of, supportive responses. The child is anxious in its explorations of the world, which can, in turn, evoke erratic responses from caregivers, and the subsequent attempt by the child to get by without the support of others.To the extent that children feel that they have a secure base, they develop in a way that expands that base for further development through the left and right cycles of the schema. This is depicted by the growth from the smaller platform at the bottom to the larger one above and by the change in cross-hatching. Similarly, for adults, a platform is some relatively safe space for taking stock of the effects of possibly risky engagements in the wider world, learning from that, and continuing to grow the platform.

Why does a platform have to grow? Why, once put into place through our development as a child to adulthood, can't it just stay the same? Why would someone—a teacher, a coach, a colleague—try to foster change?

The first answer might be that is never possible not to change. Internal events happen, e.g., we age, get ill, recover. External events happen, e.g., the financial collapse in 2007-8. The first answer then would be that we would pay attention to the way the platform needs to evolve and change in order to respond well to unavoidable change.

A second reason why we might wish to change a platform would be to counteract the limitations that we've taken on in our particular pathways of development—in our families, in our culture, in our peer relationships, in our gendered ways of working in the world. We might want to foster change to move beyond or counteract those limitations—or we might want to help someone else do so.

Both answers are complicated by the dynamic interaction that emerges out of the meeting of "inner and outer worlds" (Harris 2000; see also Taylor 2015 on Hendriks-Jansen 1996). A platform is meant to be distinguished from personality, willpower and other qualities held to be inside the person (but see think-piece on Creativity in Context). At the same time, the platform is not something external that dispenses with a developing person's self-directedness. What is the role then of the outsider—the teacher, coach, colleague—in supporting a person's platform growing?

This last issue recalls the tension identified in the introduction of these think-pieces: Although Jeremy and I believe that the frameworks and tools presented in the book are useful, we do not want you to wait for us to provide evidence of the their effectiveness. Instead, we hope that you experiment with some of them for yourself and build up a toolbox to draw from in your own research and engagement. We want, in other words, your toolbox building to be part of your platform growing.

Similarly, I only point to the complications and tension; I do not want you to wait for me to propose some resolution. Nevertheless, a few notes on possible synonyms for platform should help you think more about the term in relation to alternatives (see Alternatives Thinking and think-piece on Journeying to Develop Critical Thinking)

Synonyms?

The discussion above has pointed to studios as instances of a platform, which provide a base of security or safety for personal and professional development. A platform is also like a private universe in the field of conceptual change in science education (Annenberg Learner 2017). Conceptual change education says do not just try to teach children the correct way of thinking about science—e.g., how the planets go around the sun. Instead, recognize that students come to your classes already with a view about how those things happen. That is their private universe. It may not be correct in scientific terms, but it needs to be recognized. The lessons need to allow students to discover how their private universe runs into problems and how the more established knowledge gives them some way out, some resolution of the problems.Yet the platform is unlike a private universe in other senses. Platforms extend beyond concepts, involving our bodily arrangements, strength, coordination, stamina, and so on. They also involve our systems of relationship with others. So they are not so focused on concepts. Like the private universe and conceptual change, they are something you build on. But, unlike the private universes, they are not something to be replaced eventually with a correct view. It is as if platforms were private universes where we continue to have private universes; where we never get to some correct version.

The term scaffold might be another synonym for platform. In one sense, ironically, a scaffold was literally a platform, namely the place where they would hang people. To be taken to the scaffold was to be taken to the platform on which was erected the post that people got hanged from. In education, there is a more benign view of the word scaffold—it is more like a ladder. The teacher has to set up the ladder and lead the students to the first rung. All the rest of the rungs have already been put in place and students then climb up the ladder. That view of scaffold does not capture the picture in this think-piece of a person continuing to build upon their own platform. However, in the construction industry there are forms of scaffolding in which people can jack themselves up (Qualcraft Industries 2013). Self-scaffolding is, indeed, an apt descriptor of our bones, which are a dynamic structure having components that are constantly replenished with new components in a way that maintains their integrity as a structure, but adapts to changes in its contexts (such as new stresses strengthening bones or, as for astronauts, weakening them). Moreover, possibilities not seen or experienced before may be generated through such dynamic interaction (Slijper 1942). If scaffolding had only these last connotations and not those of a place to be hanged or a ladder set up by someone else, then there would have been no need to advance platform as a term to organize our thinking and stimulate further questions.

References

Annenberg Learner. (2017) “A private universe.” https://www.learner.org/resources/series28.html (viewed 28 Oct 2018).Bowlby, J. (1988). A Secure Base. New York: Basic Books.

Harris, T. (ed.) (2000) Where Inner and Outer Worlds Meet. London: Routledge.

Hendriks-Jansen, H. (1996) Catching Ourselves in the Act. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Mezirow, J. (1978) "Perspective transformation." Adult Learning 28: 100-110.

Qualcraft Industries (2013) "QualCraft Pump Jack System." https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rknceKw1cDA (viewed 30 Oct 2018)

Slijper, E. J. (1942). Biologic anatomical investigations on the bipedal gait and upright posture in mammals, with special reference to a little goat, born without forelegs. Proceedings of the Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen, 45, 288-295, 407-415.

Taylor, P. J. (2015) "What is a platform" https://wp.me/p1gwfa-Ji (viewed 29 Oct 2018)