OVERVIEW

This is not just another book about research and writing. Most texts on research lay out the step-by-step decisions starting with identification of the problem. Or they review the theories and methods involved in various kinds of research. Texts on writing provide guidance and exercises to improve your writing skills. In contrast, this book presents frameworks and tools to help you become more engaged in and through research, writing, and group processes.Suppose you have a specific question or a general issue that seems worth investigating. Now reflect on your level of engagement with that research. Is it important to you personally? Does the inquiry really flow from your own aspirations (as against being directed to meet the expectations of others—advisors, funders, trendsetters in the field)? Will it help you take action to change your work, life, or wider social arrangements? Will it help you build relationships with others in such action, in pursuing the inquiry effectively, and in communicating the outcomes?

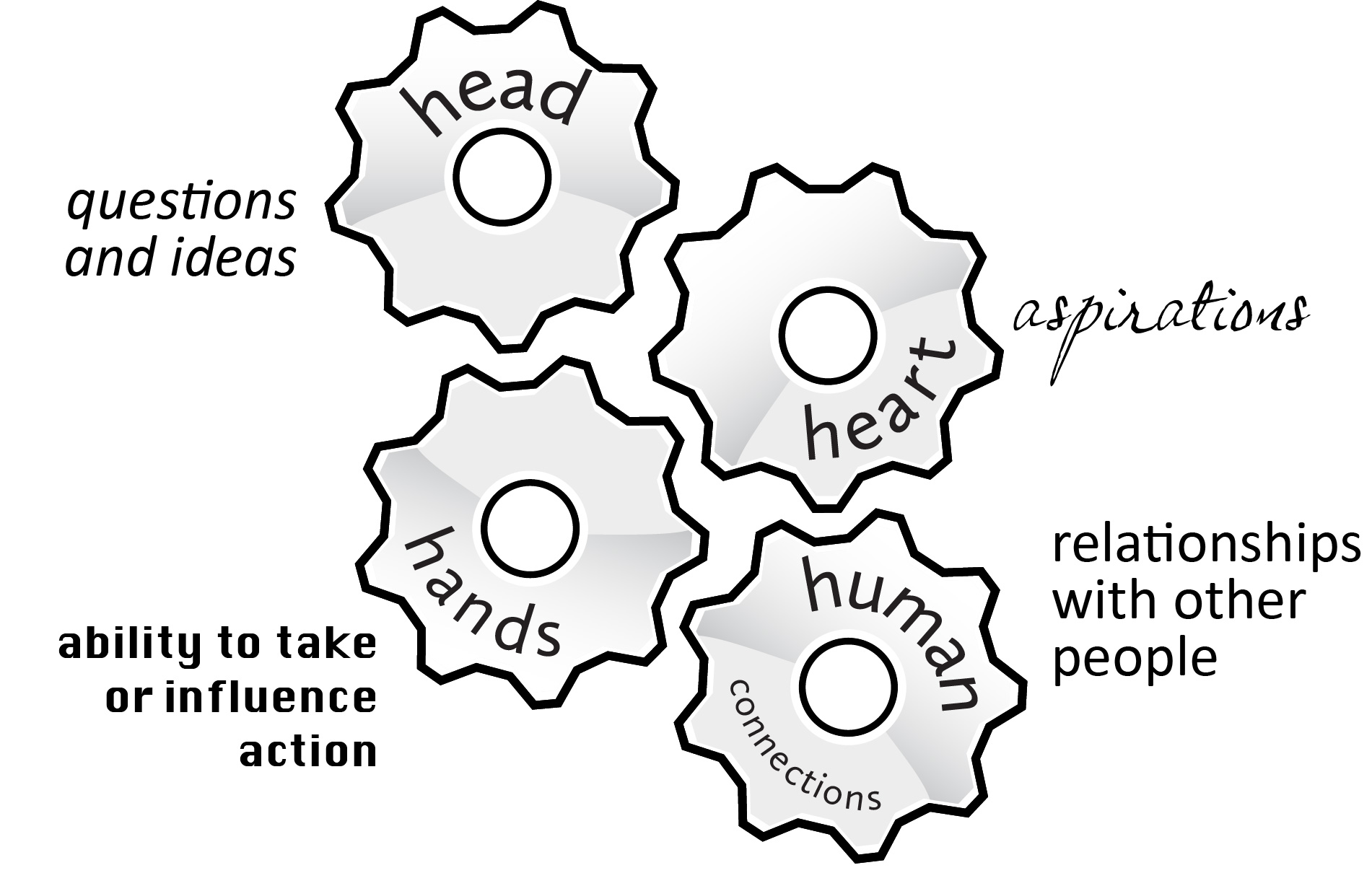

If you've answered yes in each instance, that is good to hear—in our experience these questions are not emphasized in other research and writing texts. If you answered no or maybe not to any of the questions, consider this analogy. For a car engine to move the wheels, the gears need to be engaged with each other. Similarly, for your research and writing to move along well, you need to align your questions and ideas, your aspirations, your ability to take or influence action, and your relationships with other people. These concepts can be shortened to head, heart, hands, and human connections. The frameworks and tools in this book can help you bring these 4H's into alignment. That is what we mean by engagement and by inviting readers to take yourself seriously.

Engaging the "gears" of head, heart, hands, and human connections

Notice that the book's subtitle is research and engagement, not research and writing. Indeed, the second edition adds a framework, with attendant group processes and tools, for collaborating with others to change your work, life, or wider social arrangements. As will be seen, however, the emphasis remains on taking yourself seriously, on processes through which participation in collaborative activities allows you to clarify the ideas, aspirations, priorities for action, and support you bring into engaging with others.

The approach presented in this book has emerged from our exploration and experimentation as teachers and workshop leaders in a realm we might call Critical, Creative, and Reflective Practice. The think-pieces in Part 4, which date from various periods over the past two decades, are intended to draw you into the spirit of on-going, question-opening exploration that led to this book and now to a second edition. In brief, one of us, Peter, has been teaching in interdisciplinary and non-traditional college programs since the mid 1980s. The approach presented in this book originated in a workshop-style research course in which his undergraduate students investigated issues about the social impact of science that concerned them, meaning they wanted to know more about it or advocate a change. The approach has been further developed through Peter's subsequent work in a mid-career personal and professional development graduate program where he has advised well over one hundred Master's students undertaking their final “synthesis” projects and has taught three research and writing courses that culminate in those synthesis projects. Students have brought to these courses very diverse interests and concerns—from demonstrating the routinisation of prenatal ultrasound screening to preparation for finding work as an editorial cartoonist; from adult education for low-income women to improving communication in the hospital operating room. Jeremy was one of the mid-career Master's students; his interests at the time are illustrated in part 3. Now that he has been teaching and advising in the same program, he has become an exponent of reflective practice in transition education, where transitions are pursued at the personal, community, or global levels. Given the range of projects undertaken by students in the program, the courses cannot focus on specialized knowledge in any one discipline, nor can students expect the instructor to be an expert in all of their areas of interest. Addressing the challenge of supporting students with diverse projects to take themselves seriously as they engage with others has led to the development or refinement of many tools and processes. The six innovations to follow lie at the heart of what researchers or researchers-in-training will find assembled in this book.

Six innovations

1. A framework of ten phases of research and engagement

that you move through, then revisit in light of two forms of feedback: responses by advisors and peers to the writing and oral reports you share with them; and what you learn using tools from the other phases. This sequence and iteration helps you as a researcher define projects in which you take your personal and professional aspirations seriously. (Doing so may mean letting go of preconceptions of what you ought to be doing.) These phases are presented in Part 1. Descriptions of the tools, given in alphabetical order, make up Part 2. Part 3 includes illustrations of their use in the development of a project Jeremy undertook on engaging adult learning communities in using the principles of theater arts to prepare them to create social change.2. A cycles and epicycles framework for Action Research

that emphasizes reflection and dialogue through which you revisit and revise the ideas you have about what action is needed and about how to build a constituency to implement the change. Such reflection and dialogue adds “epicycles” to the traditional Action Research cycle (i.e., problem-> data-> action-> evaluate outcomes->next steps...). The cycles and epicycles framework is presented in overview in Part 1, which includes a list of tools useful for the reflection and dialogue, constituency building, evaluation and inquiry, and planning that contribute to Action Research. Descriptions of the tools are also included in Part 2. Part 3 includes excerpts from a second project of Jeremy's, involving collaborative play among teachers in curriculum planning, which illustrate the framework by conveying the experience of someone learning to use it. A think-piece in Part 4 positions the approach in relation to sources of inspiration regarding Action Research and Participation.3. Dialogue around written work

Written and spoken comments on each installment of a project and on successive revision in response to the comments. Dialogue creates the chance for you and your advisors (or instructors) to recognize and understand perspectives separate from your own, and then revisit your ideas by putting alternatives in tension with them. If your advisors assemble a portfolio of your installments and comments, they can look back over them when they interact with you. This makes it more likely—even when they are not an expert in your project's topic—that the unfolding dialogue helps you bring to the surface, form, and articulate your ideas as a researcher. Dialogue around written work is evident in the illustrations in Part 3 and is discussed further in the think-piece on Teaching and Learning for Reflective Practice in Part 4. (You might choose to read that think-piece first if, before jumping into the practical details, you want to have a view of Peter's development as a college teacher and the journey through which the tools and processes have emerged.)4. Making space for taking initiative in and through relationships

Don't expect to learn or change without: negotiating power and standards (a “vertical” relationship); building peer (or “horizontal”) relationships; exploring difference; acknowledging that affect is involved in what you're doing and not doing (and in how others respond to that); developing autonomy (so that you are neither too sensitive nor impervious to feedback); and clearing away distractions from other sources (present and past) so you can “be here now.” These aspects of teaching-learning relationships do not always pull you in the same direction, so it is difficult to attend to all six aspects simultaneously. Instead, expect to jostle among them. (The idea that you keep many considerations in mind, but focus on a few at any given time informs the book's approach as a whole; see the think-piece in Part 4 of Teaching and Learning for Reflective Practice.)5. Creative habits for synthesis of theory and practice

A framework for that point in your life when you take up the challenge of writing something that synthesizes your theory and practice. Everyone has a voice that should be heard. The creative habits introduced in Part 1 and described in Part 2, together with the other frameworks and practices above, constitute a structure of support—including support from yourself—that enables you to find your voice, clarify and develop your thoughts, and express that voice in a completed written product.6. Connecting-Puzzling-Reflecting (CPR) Spaces

A workshop or learning activity that fosters carryover of outcomes into your work and life in the following manner. The CPR space has a topic that you explore in relation to your individual interests, aspirations, and situations. The exploration makes use of tools and processes, not only for the exploration, but also to develop connections among participants—connections that help you open up, puzzle over, and flesh out your contributions to the topic, and re-energizes you for engagements back in your workplace and communities.How to use this book?

Like a field-book, it is something you might simply refer to from time to time, looking for tools and processes to adopt or adapt in your current endeavors or for inspiration as conveyed in the Part 4's think-pieces. (For terms in Bold Face or Capitalised in the text (not in headings), readers can find details in the relevant section of Part 1, Phases, Cycles, Habits, and Spaces, in the entries that make up Part 2, Tools and Processes, or the think-pieces of Part 4.) We hope, however, that at some point you decide to move systematically through the Phases and Cycles, employ the Habits for Synthesis, and collaboratively explore CPR Spaces. These frameworks are structures intended to guide readers—whether you are a college student or a more experienced professional—as you develop as researchers, writers, and agents of change. (The first three frameworks also lend themselves to adaptation by teachers and advisors designing semester-length courses.)Of course, the kind of help derived from the book depends on where in the spectrum of researcher or researcher-in-training you lie. Just as some children learn to read with little instruction, there are some students who have little trouble learning to define a hypothesis that can be studied with the methods of their discipline and are comfortable using the standard writing conventions and publication format to report on research. If you operate at that end of the spectrum, you may view the integration of the 4H's that emerges through the frameworks and practices above as a way to help you branch out in new directions and to avoid simply continuing along previous lines. However, perhaps you are at the other end of the spectrum—you may feel alienated from the expectations of any one discipline and struggle to complete your research and writing assignments. If so, view this book as a way to keep your eye not on the supposed prize of the completed project, but on the possibility of developing a project that engages you. To find such a project you need to push aside expectations you think others have for you for long enough to explore how to connect your head with your heart, to give voice to your aspirations, to build connections with others and to change your work, lives, and wider social arrangements.

Then again, perhaps you lie in between these two poles—you might be a diligent student or researcher who eventually meets disciplinary standards, but you ask for more input in generating research questions and editing written work than your advisors like and take longer to complete a project than everyone had hoped. You may be susceptible to doubt and procrastination—am I really doing something worthwhile for society and for myself? If this picture fits, you might pay more attention to the 4H's as a way to become more confident and comfortable about the directions of research and engagement that you choose. Wherever you lie in the range of students and researchers, the variety of tools for research, writing, and group process presented here constitute an invitation to you to take yourself seriously.

There are, of course, many more tools and processes for research and for collaboration than we describe. Denzin and Lincoln (2005), Schuman (2006), and references throughout the book provide a number of entry points into the wider world of research, writing, and engagement in change. An Internet search of syllabi for research courses will yield additional texts that lay out the steps, decisions, theories, and debates involved in research in any specific field. Our approach can, however, serve as a valuable complement to specialized texts in the many pieces of scaffolding it provides for you to explore new directions of wholehearted engagement with others—and with yourself. In this spirit, your work- and life-shaping explorations should be informed and stimulated by the models of experimentation and explorations from the authors' own work that make up Part 4.

----------

Denzin, N. and Y. S. Lincoln (eds.) (2005). The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Schuman, S. (ed.) (2006). Creating a Culture of Collaboration: The International Association of Facilitators Handbook. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass.