Songs the Dinosaurs Sang

A Model Lesson for Teaching Thinking and Understanding

Through Multiple Intelligences

By: Nina L. Greenwald

Songs the Dinosaurs Sang

A Model Lesson for Teaching Thinking and Understanding

Through Multiple Intelligences

By: Nina L. Greenwald

They sensed it. Then they heard it. The sound of something big was moving toward them. As the lumbering, rhythmical stomp came closer, a heaviness filled the atmosphere. In a harmony of their own, objects trembled and vibrated in the background. Something massive was dragging things in its path as it moved, announcing its approach with sounds that had to travel the length of a great body before finally being heard. Squeals, bellows, snorts, and hurricane-force exhalations swept the surrounds. As it came into view, their hearts pounded in their ears. They stared in amazement.

An apatosaurus was standing in the middle of the room! Ten people-bodies long, it swung its crane-like neck from side to side, up and down, marking time with a reverberating stomp as it eyed a nearby plant.

Any resemblance here to a scene from Jurassic Park is purely coincidental, because all this takes place during a lesson I conduct that promotes understanding through musical and bodily-kinesthetic thinking. The creature taking up the middle of the room, whether conceived by students or educators, is a result of having thought about a central question in the lesson in which they are participating. This striking demonstration is one of several ways they communicate understanding, one of many successful outcomes of a specific instructional process.

The Lesson Model

Multiple Intelligence Theory (Gardner, 1983) provides a broader context for identifying and cultivating many kinds of gifts and talents in addition to the verbal and mathematical that have been so singularly emphasized in our culture. As Beecher (1996) reminds us, there is growing concern that educators may not be challenging today's students. There is a need for instructional models that develop students' diverse thinking potential and special strengths that lie within it.

"Songs the Dinosaurs Sang" is a model lesson. It illustrates a constructivist approach for developing and challenging students' different thinking strengths. In the contexts of musical and bodily-kinesthetic thinking, interpretation of the sounds ("songs" as they might be considered) and movements the dinosaurs made as they negotiated their primitive environments can be a basis for understanding how they adapted and survived.

The following lesson, designed for elementary students, includes a discussion of teaching/learning objectives and the process by which students use musical and bodily-kinesthetic thinking to construct understanding:

The Teaching/Learning Objectives

Musical - specifically, auditory imaging of sound, sensitivity to rhythmical patterns, vibration pitch, tone and beat

Bodily-Kinesthetic - specifically, moving the body to represent size, gait and appearance; balancing, coordinating and synchronizing movements

What sounds and movements would different dinosaurs have made and what can these tell us about how they adapted and survived?

In this lesson, understanding is based on two levels of problem solving. First, students need to determine what sounds and movements were made by dinosaurs. Then they need to use this information to make inferences about adaptation and survival.

What is meant by "understanding" is a deep kind of learning that goes well beyond simply "knowing" or being able to give the definition of something. Perkins and Blythe (1994) describe it as a matter of being able to do a variety of thought-demanding things with a topic such as finding evidence and examples, interpreting information, and analogizing and representing it in new ways. In a Piagetian context, understanding is a process of using what is known as a basis for making sense out of something new. It is the impetus for assimilation and accommodation and a result of it, a robust aspect of learning that is a continuous process of expanding, reorganizing and re-framing ways of knowing. Viewed from an information-processing perspective, understanding is about forms in which knowledge can be represented or presented, such as symbols, language and pictures, and the use of knowledge to solve problems and perform cognitive tasks.

Essentially, understanding is a constructivist or meaning-making process. Caine and Caine (1997) emphasize that "constructivist" is the way the brain "learns", and that educators need to come to terms with this. They stress that the search for meaning is innate, wired into us. It is what drives us to make sense out of our experiences which occurs through discerning patterns and relationships. The way students learn needs to be consistent with this, not in contradiction to it, which happens when teachers view their role as information dispensers and students' roles as recipients or "vessels". According to Caine and Caine (1997) the latter is a widely held (and practiced) belief set among educators that impedes students' capacities for higher-order functioning and creative thought.

The tools for constructing understanding are critical and creative thinking. The goal of understanding is growth, depth and transfer of learning. All students, including those who are more talented, can improve their abilities to use the tools of thinking and become more adept at applying what they learn to their lives. This is best accomplished by integrating teaching thinking directly into the study of content, to which constructivist approaches naturally lend themselves.

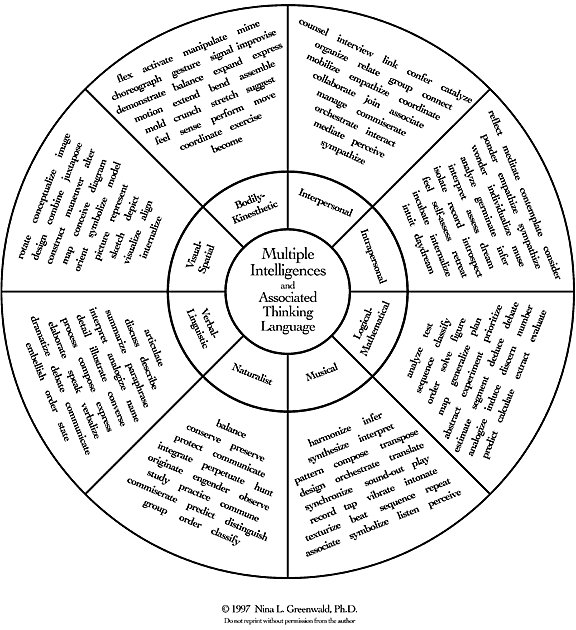

When I place people in groups according to their thinking strengths and ask them to solve a problem, their thinking process language typically reflects that strength. For example, people with musical thinking strengths use words like "compose", "orchestrate" and "transpose" to talk about ideas. I call attention to this and emphasize the importance of being alert to this language as an indication of these different thinking strengths at work. Often, students give us clues or instructions about how they prefer to think by their choice of language. I suggest that educators listen for these and make use of them to improve learning and teaching.

Attention to language led to my developing the wheel entitled "Multiple Intelligences and Associated Thinking Language" (Figure 1). Each of these eight ways of thinking can be predisposed to or characterized by particular kinds of critical and creative thinking. The wheel provides examples of thinking language for each and can be the basis for developing in-depth learning experiences.

Each kind of thinking enables a particular way of understanding. Students need to make use of the unique problem solving engine each one is and come to understand themselves as individuals who have a variety of thinking strengths they can apply to learning. There is a huge difference between students simply practicing singing, movement and drawing for example, and their being challenged to think and problem solve through the systems that underlie these capabilities. It's the latter that addresses the real function of thinking strengths and what needs to shape learning and teaching.

The lesson model presented here incorporates key aspects of teaching thinking, beginning with establishment of the focal thinking skills through which students will construct understanding. This is consistent with Type II learning which Renzulli (1977) describes as the development of students' thinking and problem solving skills and says is essential for all students, including the gifted and talented.

For this lesson, the following thinking skills are drawn from the musical and bodily-kinesthetic sections of the wheel:

associatephysical characteristics of a dinosaur with sounds and movements

interpretthe meaning of a dinosaur's sounds and movements for adaptation and survival

compose a story about dinosaur adaptation and survival based on interpretations of sound and movement

perform movements and behaviors of a dinosaur through presentation of a "soundscape"

Students demonstrate understanding on several levels: through the creation and presentation of a "dinosaur soundscape" that is a result of problem solving through musical and bodily-kinesthetic thinking; through examination of the thinking processes they used to develop their soundscape (metacognition); through discussion of ways to apply (transfer) this thinking to novel situations; and by creating concept maps (webs) that show key themes and related ideas about dinosaur adaptation and survival.

The Process

The lesson begins with a discussion of a wide range of characteristics and skills associated with musical and bodily-kinesthetic thinking. Cultivating this broader vision helps students to recognize aspects of these strengths in themselves, as distinguished from tendencies to think of them in narrow or stereotypic ways, or believing they simply do not possess them. For example, appreciating music, the ability to hear music without actually being in its presence, and singing in the shower are all aspects of musical thinking. Playing charades, model-building, and making "angels in the snow" are all related to bodily-kinesthetic thinking strengths. I ask students for examples of their own musical and bodily-kinesthetic strengths, emphasizing the nuances, and that everyone has degrees of these strengths and is capable of developing them further.

Next, students practice some musical and bodily-kinesthetic thinking. For example, I might ask them to imagine and imitate certain sounds, and use their bodies to demonstrate size, weight and length. After these "warm-ups", this question is presented to them:

What sounds and movements would different dinosaurs have made, and what could these tell us about how they adapted and survived?

Now students are placed in groups and given anatomical drawings (or pictures) of a particular dinosaur or dinosaur group, plus a bag of assorted objects (junk) for creating sounds. I ask them to think about what kinds of sounds and movements they would associate with this dinosaur and then, based on their conclusions, to compose and perform a story about how it adapted and survived. As an example of how physical characteristics can be suggested through sound and movement, I ask students to recall the "T-Rex" scene from the movie Jurassic Park -- the sounds of muffled thunder and accompanying vibrations in the ground and puddles of water, suggesting the approach of something huge and powerful!

This sets the stage to clarify their thinking challenge. First, each group will determine how their dinosaur adapted and survived based on sounds and movements they associate with the pictures. Next, they will compose and perform a "soundscape" to demonstrate this using their voices and bodies, the junk, and other things in the room. Tape-recorded sounds of the rain forest playing in the background will help evoke a "dinosaur ambiance".

To reinforce the thinking emphases, the following guiding questions are written on the board. The highlighted thinking processes are defined and students are asked to give examples of how they have used them:

ï What sounds do you associate with physical characteristics of your dinosaur and why?

ï How would you interpret the meaning these sounds? What do these sounds tell you about this dinosaur?

ï Based on your interpretations, what is a story you can compose about how this dinosaur adapted and survived?

ï How will you perform your story?

We also talk about how these thinking processes are part of musical and bodily-kinesthetic intelligences: for example, how music can be associated with ideas, such as peacefulness, action and mystery; how music is a way of interpreting or explaining ideas; how people compose tunes to express feelings and ideas; kinds of compositions that have been created by well-known composers like Mozart, John Williams, Carly Simon; how actors, dancers and gymnasts use their bodies to perform ideas. This discussion invites students to contribute what they know and to elaborate on one another's ideas.

As students proceed with their thinking task, teachers have an important role to play. Through modeling and coaching, they help students assume the role of problem solver, then require them to take on the responsibility of using these skills on their own. For example, posing questions like these help students shape their thinking strategies: What are you thinking about? What's another question you might ask about this? What hunches do you have about this? What could help you understand this better? Modeling is also a primary way teachers foster a culture or climate of thinking in their classrooms. All students can grow intellectually in this climate. Gifted and talented students need and are especially responsive in such a climate.

After each soundscape is presented students think about this question: based on this presentation, what do you think you know about this dinosaur? The guiding questions serve as a focus for discussion and students' ideas are recorded on chart paper. Again, the role of the teacher is as facilitator, guide or metacognitive coach, in contrast to "information dispenser" in charge of what students learn. The teacher continuously raises questions that challenge students' thinking and shape self-directed learning so that they can acquire appropriate information and develop ideas on their own. Questions like "What do you Know or think you know?", "What do you Need to know?", and "How can you Find out?" help students sort through potential interpretations and structure understanding. To help them re-evaluate their thinking processes, students can keep an ongoing "K-N-F" chart which they can continuously revisit.

Following these discussions, I ask metacognitive and transfer questions. These questions re-direct students back to the focal thinking skills to reflect on how they used them and can apply them to new situations. For example:

(M) What kinds of thinking helped you understand the sounds your dinosaur would have made? (making associations)

(M) How did these sounds help you understand how your dinosaur survived? (making interpretations)

(M)In what other ways could you present your dinosaur story? (perform)

(T) How can music help you learn about other things you are studying?

(T) What other things, what else might be better understood through sound?

Based on their own thinking plus ideas from the discussions, each group creates a concept map or web of ideas about dinosaur adaptation and survival. The maps clarify key themes that have emerged for students and also help teachers to identify broad themes that can be studied across curriculum: for example, "relationships between characteristics of living things, adaptation and survival", "the importance of maintaining a sound ecosystem for the preservation of contemporary species" or "unsolved mysteries in our world".

In the thinking classroom, any activity is a potential bridge for further exploration. For gifted students, who need opportunities for extended learning, creating a concept map can be a catalyst for individual and small group investigation, or what Renzulli (1977) defines as Type III learning. The student becomes a self-directed, first-hand inquirer and pursues an area of interest in depth, from problem definition, to solution generation, to the presentation of findings to real audiences. The process is constructivist, the role of the teacher facilitative, about which Renzulli (1982) says: "The students' teachers also become experts, but not in the content that their students are studying. They become expert facilitators and learn how to guide students through the process of a Type III study. It is a challenging role to play and requires a transition from being 'sage on the stage' to 'guide on the side'."

Hats off to the music-makers!

At the heart of the model lesson presented here is an instructional strategy for turning on eight different "engines of the mind" in students. As the model illustrates, the language of critical and creative thinking associated with each of these thinking systems can be integrated into lessons and become the key vehicles through which students construct understanding. As the "music-makers" will attest, (the many students, teachers, and their students, who have participated in this model lesson) a result is learning that goes well beyond simply "knowing".

Along with gaining a better grasp of how different thinking perspectives work to solve problems, people realize that within each there is rich potential for possessing many kinds of gifts and talents. For this reason especially, our concept of what it means to be gifted and talented needs to be open and continuously expanding. Our hope must also be that all students, when given opportunities to think through their many intelligences, will learn far more than we yet know how to teach.

© Nina Greenwald, August 2001

Greenwald, N.1998. Songs the Dinosaurs Sang! A model for teaching thinking through multiple intelligences. Gifted Child Today, Nov/Dec, Vol 21, No.6.

References

Beecher, M.(1996). Developing the gifts and talents of all students. Mansfield Center, CT: Creative Learning Press.

Caine, R.M. & Caine, G. (1997). Education on the edge of possibility. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind. NY: Basic Books.

Perkins, D. & Blythe, T. (1994). Putting understanding up front. Educational Leadership, 51(5), 5-6.

Renzulli, J. S. (1977). The enrichment triad model: A guide for developing defensible programs for the gifted and talented. Mansfield Center, CT: Creative Learning Press.

Renzulli, J. S. (1982). What makes a problem real? Stalking the Illusive meaning of qualitative differences in gifted education. Gifted Child Quarterly, 26(4),148-156.