Briefing for the proposition: Goldberger’s discovery could not prevent pellagra in the 1910’s and 20’s in the United States, but could in the 1930’s.

The proposition is supported.

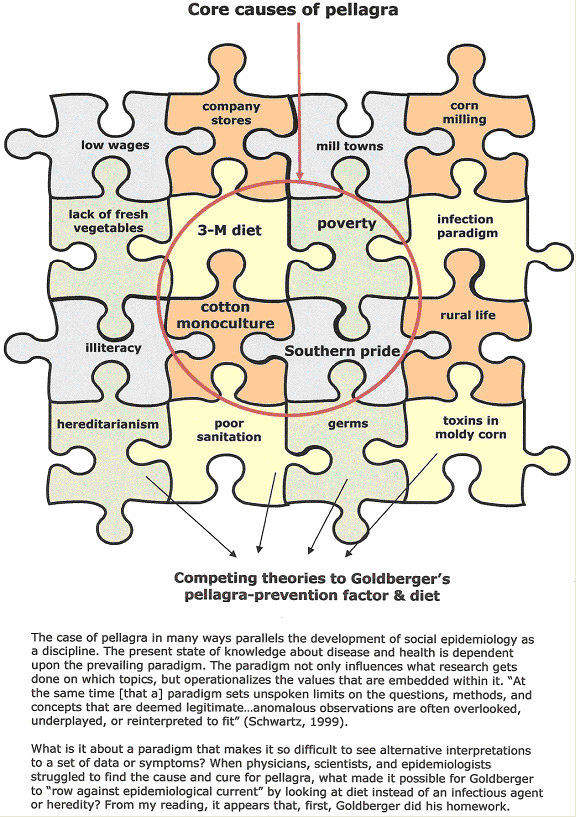

Goldberger’s discovery was that pellagra was a nutritional deficiency disease -- namely a lack of niacin in the diet. Initially I addressed the proposition by means of the following knowledge claim: that hereditarianism (characterized by Chase in the scenario as having contributed to undermining the search for the true cause of pellagra) was only one of a complex of factors that prevented understanding the cause of pellagra and delayed its cure. Through extended research and reading, I arrived at the conclusion that the proposition could be supported; that is, Goldberger’s dietary theory alone could not have prevented pellagra in the 1910’s and 20’s, I found, because multiple social, cultural, and economic factors - as well a documented skirmish with eugenic thinking - were in place to prevent it. On the other hand, changes had taken place by the 1930’s that made the plausibility of the P-P factor more persuasive – e.g. improvements to the body of knowledge in nutrition (that led to the fortification of foods) and medicine, a waning of the influence of the prevailing “infection” paradigm, several natural catastrophes and government responses to them, etc. As evidence for the above, I offer the following points:

As early as 1915, when the Rankin Prison Farm experiment results were published, the link to diet was made clear. Although the specific niacin deficiency was not known until later, it was not for lack of that precise mechanism that people continued to suffer needlessly.

Cultural factors played a role in the search for a cause for pellagra. There were a number of Italian immigrants in the South at the time pellagra made its appearance. Initial efforts to trace the cause of the disease pointed to Italian immigrants as pellagra was known to occur in Italy. Leslie reported that in the Literary Digest of 1913, there was “ample evidence to discard the dietary factor. The writers announced that the ancient Italian doctors were mistaken about the basis of pellagra in spoiled corn and they were sure that pellagra was an infectious disease imported from Italy along with the ‘hordes of immigrants who have arrived in the past 30 or 40 years’” (2002, p. 194). Kunitz made a salient point in his article on hookworm and pellagra when he states that “often the investigator’s values and ideology rather than the intrinsic nature of the disease itself determine the approach to understanding etiology, cure, and prevention (1988, p. 146).

Social and economic factors in the South were such that, as Chase noted, work on finding a cause and cure for pellagra was influenced by the fact that it was a disease confined to the poor. Had the Davenports and the Henry Fairfield Osborns been afflicted instead of the Jukes and the Kallikaks, he believes work on the disease would have begun earlier and attracted more resources. It is only when the production and operation of the mills in the South began to suffer as a result of absenteeism that a more concerted effort was made to understand the disease of pellagra. In addition, the manner in which statistics were gathered could have had an effect on how widespread and critical the disease appeared. In general, outside of institutions such as asylums and orphanages, people who contracted pellagra would not have turned up in a doctor’s office. Elizabeth W. Etheridge reported that only one pellagrin in six ever consulted a doctor, so if physicians sometimes insisted that pellagra was not very widespread, or, indeed, occasionally boasted they had never seen a case, they had good reason (1972, p. 131).

Pellagra in the medical paradigm of the day

In the early part of the century, a number of diseases were understood to be caused by microbes and thus earned the label “infectious diseases.” Smallpox, measles, rabies, and tuberculosis were among the diseases that established the idea that bacteria too small to see were responsible for disease. The infection theory marked a departure from previous ideas about the causation of the debilitating disease of pellagra – the earliest investigators had concentrated on the connection of corn with the incidence of pellagra. It was thought by European doctors that moldy corn must produce a toxin that was ingested with cornmeal. Etheridge wrote that “until about 1905, public health work in the Southeast was based on the idea that disease was caused by filth…Public health officials of the South, reflecting the new advances in medicine, embraced the bacteriological concept of disease” (1972, p. 104). In an ironic twist, Leslie noted that while in the physician’s care, patients were given the balanced diet that alone would have restored them to health yet they were forced to undergo treatments that ranged from the administration of arsenic to blood transfusions, salt baths, and even static electricity (2002, p.188).

Given the era in which pellagra reached almost epidemic proportions, it was “fashionable for the critics of Goldberger to think that pellagra was a transmissible infectious disease” (Rajakumar, 2000, p. 4). Using this as their starting point, the Thompson-McFadden Pellagra Commission of 1912 concentrated its efforts in house-to-house surveys of pellagrous families in Spartanburg, South Carolina. The Commission considered a host of insects to be candidates for the spread of infection - ticks, lice, bedbugs, cockroaches, horseflies, fleas, mosquitoes, buffalo gnats, houseflies and stable flies – but eventually had to rule out all but the housefly and stable fly. Nevertheless, the germ theory had taken hold; when it was found that most pellagrins lived in circumstances with poor sanitation, an almost ideological connection was made.

Goldberger’s work on the Southerner’s “3-M” diet – meat, meal, and molasses – was met with resistance and ridicule on a number of fronts, not all of them medically-based. The idea that an epidemic disease in certain areas of the country was associated with poverty and a monotonous diet was embarrassing for the South; hence the theory was not accepted and was fought politically and intellectually (Bollet, 2004, p.153). The letter that Goldberger sent to the Public Health Service in Washington about a projected increase in pellagra in 1921 made page one in the New York Times. It caught the attention of President Warren G. Harding and set in motion events that called into question not only the lack of nutrition in the South’s favorite diet, but the wisdom of cotton as monoculture.

Pellagra and hereditarianism

In terms of the range of causative factors that raged in the debate about pellagra, the heritability claim was a minor one and seems to have been pursued chiefly by Charles Davenport. As Chase noted, Davenportcould not quite make the case for pellagra as an inheritable disease, but instead said it had a genetic component. He joined with “the infectionists” in calling pellagra a communicable disease but stated that “how the communicated ‘germ of the disease’ progress[ed] in the body depend[ed] in part upon constitutional factors” (1977, p.214).

Davenport’s ‘proof’ consisted of a series of family pedigrees that showed pellagra clustered in families more often than the general population expectation (Joseph, 2006, p.88). Goldberger objected that these charts merely reflected a false correlation between the living conditions (i.e. poor sanitation) of families with pellagra. J. Joseph wrote that the conclusions Davenport and others drew from these ‘pellagra family pedigrees’ were a classic example of the fallacy of inferring genetic causation from the results of family studies (p.88).

N.A. Holtzman stated in his article “Genetics and social class” (2002) that genetics cannot explain the perpetuation of complex traits in one class in succeeding generations. He observed that even Elizabeth Muncey, Davenport’s colleague at the Eugenics Record Office, concluded “the data collected shows no evidence of direct heredity. There may, however, be an hereditary predisposition to the disease in those families in which chronic gastro-intestinal symptoms have existed for several generations” (p. 530). After reviewing what genes actually do and how heritability is actually measured, Holtzman agreed with Garland Allen, whom he quoted: “By suggesting a genetic cause for persistent or recurrent social dilemmas, hereditarian theories suggest that the victims, not the social system, are the cause of their own problems…” (p. 531).

Martin Pernick (1997) wrote about the connection between public health and eugenics in the early 20th century. He makes a number of provocative points, including the assertion that eugenic methods were often modeled on the infection control techniques of public health. He noted that medical justifications for racial slavery predated Darwin and Galton, and even in its heyday, eugenics had no monopoly on scientific racism. Rather, it merely medicalized broader cultural biases that existed at the time.

Goldberger’s discovery finds traction in the 1930’s

As with the search for the causes of pellagra, there were many direct and indirect factors that contributed to Goldberger’s views finally being accepted in the Thirties. Among them were:

The Mississippi flood of 1927.

When this natural catastrophe struck, there were three threats to health that threatened the counties in the 12 states that were under water: malaria, typhoid, and pellagra. Quinine and typhoid vaccines were distributed to the affected citizens, and Goldberger and Sydenstricker embarked on a tour of the flood area. Their recommendations to the Red Cross included the provision of thousands of pounds of brewer’s yeast to the flood victims. The effects were almost miraculous, although cases of pellagra continued to grow in the next few years. Nevertheless, the flood did heighten awareness of the social and economic aspects of pellagra (Etheridge, p. 183).

The drought in 1930-31.

Learning from the success of the flood yeast distribution program, the Red Cross again freely gave away yeast to drought victims. In addition, Etheridge (p. 196) related that the Red Cross distributed garden seeds as part of a high profile grow-your-own-food campaign. This one intervention had many positive effects: not only were people getting the leafy vegetables that helped to prevent pellagra by growing their own food, but they were able to can and bottle the excess as well. The campaign changed attitudes about gardening, with many Home Demonstration agents fanning out to teach people about home canning. In addition, efforts were made to teach people to supplement the 3-M diet, rather than trying to change it in toto.

Food fortification.

The voluntary enrichment of bread began in 1938. Park (2000) suggests that food fortification had an even greater impact on the elimination of pellagra than did the changing economic conditions in the South.

Government intervention.

Indirectly, government initiatives such as the food relief programs of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration and the mass adult education programs of the Farm Security Administration in the early 30’s helped to promote healthy eating by providing practical items such as a wagon, a mule, and a cookstove (Etheridge, p. 204).

There was increased funding for public health education in 1935, particularly with the passage of the Social Security Act of 1935. This legislation “expanded financing of the Public Health Service and provided federal grants to the states to assist them in developing their public health services. Federal and state expenditures for public health actually doubled in the decade of the Depression” (Board on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention & the Institute of Medicine, 2003).

New knowledge of nutrition from scientific and medical communities was disseminated to the public at large. An emphasis on scientific nutrition was pushed in the name of patriotism, according to George Rosen (1993, p. 393). Government action in relation to nutrition included the provision of school lunches, and the food stamp program.

Actions that could have been taken by people or groups pushing against the infection or hereditarian theories at the time, although purely speculative, include:

1. More visibility for views that did not coincide with the moldy corn theory in prominent medical congresses such as the National Conference on Pellagra in 1909 in Columbia, Georgia.

2. Less parochialism in the race for the cause of pellagra. Etheridge noted that the Southern Medical Association “cheered on the contestants in this scientific race. It held out as reward for the winner – the discoverer of pellagra’s specific origin – the association’s research medal. It fervently hoped that a Southerner, one of the association’s own members, would win the prize” (p. 29).

3. Successfully gaining patronage from a philanthropist organization or individual. A few years earlier in 1909, John D. Rockefeller had made a million dollar gift to the Southern states for the eradication of hookworm disease to be used over a period of five years.

(diagram by jrc)

He read the literature on pellagra, both home grown and international. He was aware of previous (ignored) work by Dr. R.M. Grimm, who, with Dr. Claude Lavinder, was sent to the South by the Public Health Service in 1911. Grimm’s fieldwork led him to observe the diets of people afflicted by pellagra as well as other factors such as their poor living conditions and ample insect life. When Goldberger began to hone in on the meat, meal and molasses diet, he was looking for what was missing from the diet, rather than at the foods currently consumed (Kraut, 2003).

Much has been made of Goldberger’s status as a non-Southerner: that he was able to make observations others missed because they seemed so “natural” to the way of life in the South. Goldberger was described as maintaining an open mind when he began his assignment. He could have ascribed to the infection theory as many around him did, but instead he methodically visited the institutions, orphanages, mill villages, and other places where pellagra cases were rife, making meticulous notes and trying to see the relationships between the disease and its choice of victims. His inclusion of the economic and social aspects of pellagra foreshadowed a new way of looking at disease.

Were Goldberger alive today, he might be numbered among the epidemiologists who advocate an ecosocial perspective, or eco-epidemiology. Eco-epidemiology “addresses the interdependence of individuals and their connection with the biological, physical, social, and historical contexts in which they live” (Schwartz, 1999, p. 26). Ecosocial theorists “seek to integrate social and biological reasoning and a dynamic, historical, and ecological perspective to develop new insights into determinants of population distributions of disease and social inequalities in health” (Krieger, 2001, p. 674). These multi-layer approaches are more dynamic and systems-like than the single-germ theory or miasmatist theories that preceded them, but they also lack the analytical tools and methods that sufficed for earlier “risk factor” analyses. Kaplan highlights the need for “better sources of data and for new methods to allow the stitching together of data from a variety of sources, levels, periods, and places. Quilts from such data stitched together by using such new techniques, and incorporating sensitivity analyses and other techniques, could considerably strengthen our ability to turn the complex models of social epidemiology into useful analytical models of disease processes in persons and populations” (2004, p. 127). All of these writers stress the need for theory with attendant concepts, methodologies, and analyses.

It cannot be an exaggeration to say that, without Goldberger, the new paradigm of eco-epidemiology might have been considerably delayed. Although trained in the norms and practices of his day, he managed to question what seemed “natural” and given. One wonders when the maverick for our time will appear!

References

Board on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention & the Institute of Medicine. Who will keep the public healthy? Educating public health professionals for the 21st century. (2003). Retrieved on 3/30/06 from National Academies Press at http://fermat.nap.edu/books/0309089662/html

Bollet, A.J. (2004). Plagues and poxes: the impact of human history on epidemic disease. NY: Demos Medical Publishing. E-book retrieved on 2 March 2006 from NetLibrary.

Chase, Allen. (1976). “A Few False Correlations = A Few Million Real Deaths: Scientific Racism Prevails Over Scientific Truth.” The Legacy of Malthus. New York, Knopf.

Etheridge, E.W. (1972). The Butterfly caste: A social history of pellagra in the south. Westport: CT., Greenwood Publishing Company.

Holtzman, N.A. (2002). Genetics and social class. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 56, 529-535. Retrieved on 10 March 2006 from jech.bmjjournals.com

Joseph, J. (2006). The Missing gene: psychiatry, heredity, and the fruitless search for genes. NY: Algora Publishing. E-book retrieved on 2 March 2006 from NetLibrary.

Kaplan, G. (2004). What’s wrong with social epidemiology, and how can we make it better? Epidemiologic Reviews, 26: 124-135. Retrieved on 10 March 2006 from Academic Search Premiere database.

Kraut, A.M. (2003). Goldberger’s war: the life and work of a public health crusader. NY: Hill & Wang.

Krieger, N. (2001). Theories for social epidemiology in the 21st century: an ecosocial perspective. International Journal of Epidemiology, 30: 668-677. Retrieved on 10 March 2006 from Academic Search Premiere database.

Kunitz, S.J. (1988). Hookworm and pellagra: exemplary diseases in the New South. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 29, 2: 139-148. Retrieved on 12 March 2006 from JSTOR database.

Leslie, Chris. (2002). “Fighting an unseen enemy”: The infectious paradigm in the conquest of pellagra, Journal of Medical Humanities, 23 (3/4) : 187-202. Retrieved on 10 March 2006 from Academic Search Premier database.

Park, Y.K., Sempos, C.T., Barton, C.N., et.al. (2000). Effectiveness of food fortification in the United States: the case of pellagra. American Journal of Public Health, 90 (5): 727-738. Retrieved on 29 March 2006 from Academic Search Premier database.

Pernick, M.S. (1997). Eugenics and public health in American history. American Journal of Public Health, 87, (11):1767-1772. Retrieved on 4/1/06 from Academic Search Premiere database.

Rajakumar, K. (2000). Pellagra in the United Stated: a[n] historical perspective. Southern Medical Journal, 93 (3): 272-277. Retrieved on 3/8/06 from Academic Search Premiere database.

Rosen, G. (1993). A history of public health. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Schwartz, S., Susser, E. and Susser, M. (1999). A future for epidemiology? Annual Review of Public Health, 20: 15-33. Retrieved on 10 March 2006from Academic Search Premiere database.

Sydenstricker, V.P. (1958). The History of pellagra, its recognition as a disorder of nutrition and its conquest. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 6,(4):409-141. Retrieved on3/8/06 from Academic Search Premiere database.

(original page by jrc)