New England Workshop on Science and Social Change

Background and Rationale for each objective , including how it will be achieved and evaluated

The New England Workshop on Science and Social Change (NewSSC) organizes innovative, interaction-intensive workshops designed to facilitate discussion, teaching innovation, and longer-term collaboration among faculty and graduate students who teach and write about interactions between scientific developments and social change.

Specific objectives of NewSSC

1. Promote Social Contextualization of ScienceTo promote the social contextualization of science in education and other activities beyond the participants' current disciplinary and academic boundaries.

2. Innovative workshop processes To facilitate participants connecting theoretical, pedagogical, practical, political, and personal aspects of the issue at hand in constructive ways.

3. Training and capacity-buildingTo train novice and experienced scholars in process / participation skills valuable in activity-centered teaching, workshops, and collaboration.

4. Repeatable, evolving workshops To provide a workshop model that can be repeated, evolve in response to evaluations, and adapted by participants.

5. Tangible outcomes and experiences developed beyond the workshopFor participants to go on to build on the tools and processes of the workshop, on connections made among participants, and on their contributions to the issue at hand, buoyed by the enthusiasm, hope, resolve, and courage that is generated by the learning, interacting, sharing, connecting, and communing that happens during the workshop.

Related workshops organized through the Critical and Creative Thinking and Science, Technology & Values Programs at UMass Boston

Bibliography

Endnotes

Previous versions of background & rationale

Objective 1. Promote Social Contextualization of Science

To promote the social contextualization of science in education and other activities beyond the participants' current disciplinary and academic boundaries.

Background and rationale to objective 1

Since the early 1980s scientific developments and their potential implications have been made more accessible to the public. The popularization of science through newspaper journalism, television documentaries, and book publishing has flourished. During the same period, concerns that K-12 students become more literate in the established bodies of scientific knowledge have led to new initiatives at the national level in science education (AAAS 1997, Montgomery 1994). Many innovations have centered on "student-active learning" (McNeal and D'Avanzo 1997) that fosters learning of concepts by guiding students to (re)discover them for themselves (e.g., Jungck 1997). Some initiatives, however, have adopted a broader social outlook, especially those attempting to integrate science into college-level liberal arts curricula (Gilbert 1997). Texts, courses, and software have appeared that enliven the facts and theories by presenting the historical and social context in which they were established (e.g., Paul 1995, Hagen et al. 1996).

It is fair to say, however, that the potential for studies of science in its social context to inform and be included in science education and informal outreach activities is still relatively undeveloped. I recognize that this is a contentious endeavor-during the 1990s much publicity was given to claims that humanistic and social scientific studies of science and technology contribute to "anti-science" sentiments (e.g., Gross and Leavitt 1994). Nevertheless, against these claims, it should be noted that STS scholars interpreting science in its social context have often formulated perspectives unavailable to, or underdeveloped by, scientists, and, on this basis, made contributions valued by scientists to discussions about scientific and technical developments. (A notable example is Paul's [1997] history of PKU screening which shows that the certainty of severe retardation has been replaced by a chronic disease with a new set of problems.) In this spirit, the initiators of the Human Genome Project reserved a small, but significant fraction of the Project's budget for studies of the ethical, legal, and social implications of genetics. It should also be noted that some scientists are very comfortable using STS perspectives in their teaching and writing (e.g., Doran and Garrett 2005, Fausto-Sterling 2000, Gilbert et al. 2005).

In teaching close examination of concepts and methods within any given area of the life and environmental sciences can stimulate students' inquiries into the diverse social influences shaping that science. Social contextualization can, in turn, suggest alternative lines of scientific investigation. This two-way interaction or "reciprocal animation" between science and social contextualization of science enlarges significantly the sources of ideas about what else could be or could have been in science and in society (Taylor 1997, 1998, 2003). In this spirit, participation in the workshops will be solicited from scientists and science educators as well as from STS scholars. This broad vision of critical thinking about science in its social context has informed a series of workshops and seminars organized by the Programs in Critical & Creative Thinking and Science, Technoogy & Values at University of Massachusetts Boston.

Achieving and evaluating objective 1

a. Educational/outreach innovations: Within six months of the workshop's completion participants will be expected to submit new syllabi and curriculum units[1] (primarily for college-level courses) or outreach activities (e.g., hosting a citizen forum on a science-based controversy[2]). If funds are available, as a token incentive, a stipend to defray travel and accommodation will be made contingent on receipt of these contributions.[3] The contributions will be revised in response to constructive comments from the advisory group and workshop participants before being linked to an expanding compilation of Online Resources for Science-in-Society Education and Outreach on the workshop website.[4] Attention will be drawn to the submissions through i) appropriate web newsletters and listservs (e.g., Listserv for the International Society for the History, Philosophy, and Social Studies of Biology [ISHPSSB], Technoscience, etc.; and ii) papers and sessions at meetings.[5] In the spirit of open source software, the Online Resources site will encourage others to use and adapt these innovations and to report outcomes at newssc.blogspot.com.

b. Workshop topics: These have been chosen so as to ensure that the social shaping of science and the influence of science on social processes are firmly in the center and open up issues that concern scientists, STS scholars, and science educators (see sect. II). A positive assessment of this choice of topics will be evident in i) participants from STS, science, and science education applying to attend the workshop; and ii) funder's approval of funding proposals.

c. Mix of Participants: Participants must apply to attend and will thus self-select for interest in promoting social contextualization of science, in the workshops' specific topics, and/or in the interaction-intensive workshop format (see objective 2). Applications will be solicited by notices in the newsletters and listservs of STS societies (see a, above) and by direct contact with people recommended by "veterans" of previous workshops and by others. In addition to the facilitator, evaluator, and P.I./organizer, there will be eleven other participants, who will be chosen from the applicants by the organizer and advisory group. The target will be for science educators and scientists to match the number of STS scholars. (Of course, people who apply may already span more than one of those areas and that the workshop will further that blurring of identities.) Also, in light of objective 3 (on training, see below), the target is for 3-4 of the participants to be graduate students (including one as a workshop apprentice).

d. New interdisciplinary research projects and collaborations: It is hoped that interactions during the workshop (see objective 2 below) will stimulate not only new educational and outreach activities but also research projects and collaborations-indeed, changes in one's teaching are often motivated by new research and writing interests. This outcome, however, will be a "bonus." It cannot be guaranteed because it depends to some degree on serendipitous connections, and it is hard to evaluate, because it requires a longer gestation than six months. Nevertheless, participants will be asked to report on any developments after six months or subsequently and these will be recorded on the workshop website.

Objective 2. Innovative workshop processes

To facilitate participants connecting theoretical, pedagogical, practical, political, and personal aspects of the issue at hand in constructive ways.

Background and rationale to objective 2

The premise here is that connecting these different dimensions of participants' work is fruitful in relation to their taking away knowledge, skills, and interest in crossing boundaries (between disciplines and between the academy and wider civic engagement) and then experimenting with concepts and teaching approaches they have encountered. This, in turn, should contribute to their educational and outreach efforts promoting the social contextualization of science (objective 1).

In this spirit, during all the previous workshops the participants have been led-or have led each other-through activities that can be adapted to college classrooms and other contexts, allowing them to share insights, experience, experiments, struggles, and plans. The more structured activities were complemented by opportunities for individual reflection, acknowledgement of tentative insights, and unplanned developments.[6] The title of the "Helping each other..." workshops emphasized this premise about group interaction and workshop process. The small size, intensive interaction, and evolve-as-we-go format of the "Helping each other..." workshops and the 2004/5 workshops have been designed to catalyze collaborations among the participants, in recognition of the fact that people need not only ideas and tools, but also continuing support and inspiration as they weave new approaches into their work.

Achieving and evaluating objective 2

These features of previous workshops just mentioned were well received[7] and form the basis for this proposal's two workshops, with some modifications or refinements made in response to the workshop evaluations.[8] An advisory group for the ongoing series of NewSSC workshops will review evaluations, make concrete suggestions for modifications, and help the organizer keep evaluation comments and suggestions in mind between and during the workshops.[9]

Components of the proposed workshops

Roles of facilitator, participant-evaluator, and graduate student apprentice

Facilitator. This role allows the organizer to be an active participant but not the center of interactions or lightning rod of responses to the workshop dynamics. The facilitator can attend to the many subtle conditions that make a workshop succeed in the sense of engaging participants in carrying out or carrying on the knowledge and plans they develop. These conditions, which range from making sure that "quiet spaces that occur are not immediately filled up" to "the process, as a learning community, enables participants to ask for help and support during the workshop" (Taylor 2000a), are not easy for an organizer-participant to keep on top of. Evaluation of the workshop also benefits from the observations from a somewhat detached position that a facilitator can contribute.

Participant-evaluator.Evaluation is essential to social learning about and evolution of workshops like these (objective 4, below). Participation allows an evaluator to address the first three goals and audiences of evaluations (see objective 4) and to contribute to formative (during the process) as well as summative (after the fact) evaluations.

Graduate student apprentice. Before, during, and after the workshop, the apprentice will be included in discussions about the development of the program and, as a contribution to the development of the workshop community, will check-in with the other graduate students. During the workshop, this person will also take care of minor logistical matters, so the organizer can concentrate on participating and the facilitator on facilitating.

Pre-workshop development of the workshop community will be based on telephone conversations, on pre-circulated papers and profiles (deposited on the workshop website), and on use of the workshop listserv. Participants will indicate which of their submissions has most priority to increase the chance that all participants have read a common selection of pre-readings before the workshop.

Program. This will be sketched out in advance by the facilitator and organizer, in consultation with the advisory group. Based on past experience it is expected that the workshop should unfold in the following phases:

Day 0 - Arrivals

Day 1 - Exposing diverse points of potential interaction

Day 2 - Focus on detailed case study & Excursion for unstructured conversations

Day 3 - Activities to engage each other in our projects

Day 4 - Activities to engage each other in our projects (cont.) & Taking stock of the experience.

During the workshop the program will be fleshed out and evolve as the facilitator sees opportunities and consults with workshop organizer and participants. (For an example from a previous workshop, annotated to show the purpose of various activities, see www.stv.umb.edu/newssc05.html#program.) The participants' experience of contributing to thegeneration of the workshop program also addresses objective 3, below.

Autobiographical introductions, centered around how each participant has come to be working on the workshops' theme in some sense and/or has chosen to participate in this workshop. [10] Material emerging in such autobiographical statements and sessions provides more and different context than formal presentations-We know more than we are usually able to say, and opening this to exploration in subsequent conversations and sessions is an important basis for participants (inter)connecting their work. When people hear what they happen to mention and omit in telling their own stories, they gain insight into their present place and direction. The workshop organizer will begin, and in doing so provide some context for the workshop. [11]

Activities to bring ideas to the surface and into focus (e.g., Use of Guided Freewriting [Elbow 1981] after the autobiographical introductions to allow people to identify their personal goals, followed by a Go around, in which each person states "One thing I hope to have worked on by the end of the workshop").

Case study, chosen to focus attention on key issues related to the workshop topic, allow participants to explore commonalities and differences around a concrete case, and serve as the basis for a model of experiential sessions (see below). The case study and the instructions for the experiential session should be read as homework before the session. [12]

Experiential sessions, that is, sessions in which, instead of participants telling us what they have thought or found out, they will lead other participants to experience the issues and directions they are exploring and the tools they use to help others think critically about them. Participants who haven't proposed a session in advance might invent one during the workshop. In any case, everyone will get an opportunity to expose their work as the workshop develops. This could include more conventional presentations of participants' work, but, if the pre-workshop community building is effective, there should be less need for this. These sessions provide models for participants to adapt in their own teaching and outreach activities.

Time for individual library research and writing.

Time for reflection, and for one-on-one discussions. This is essential after sessions that require active participation. [13]

Taking stock (of what we have accomplished--together or individually--and what could follow), including

- closing activity each day (e.g., Freewriting to reflect on "What is stabilizable and what needs more playing with." Facilitator leads participants in a go around, in which they state: 1. Something that is stable/ solid/ clear for them; 2. something they're pleased at having sorted out; 3. something they need to chew on more);

- formative (during the process) evaluations

- workshop closing with multi-audience evaluation

- Immediate post-workshop meeting of facilitator, evaluator, organizer, and any members of the advisory group who participated to exchange comments on each activity and each component of the workshop process.

- Virtual check-in. At a pre-arranged time window 1, 3, and 6 months after the workshop, participants will check in by email to the workshop listserv about progress on their educational and outreach innovations and other reflections.

Objective 3. Training and capacity-building

To train novice and experienced scholars in process / participation skills valuable in activity-centered teaching, workshops, and collaboration.

Background and rationale to objective 3

The premise here is that scholars who have a repertoire of process or participation skills are more comfortable and productive in organized and informal collaborative processes (Taylor 2000b), and are more likely to see new opportunities, take initiative, and experiment with the educational and outreach models they have been introduced to, in particular, models for promoting the social contextualization of science. This objective is a partial antidote to what some perceive as the insularity of STS scholarship (but see Martin and Richards 1994).

Achieving and evaluating objective 3

It is difficult to convince scholars of the value of explicit process or participation skills before they have experienced well-facilitated group process, so being able to pursue this objective depends on the good will of those who attend and their interest in the topic carrying them along until any prior skepticism is countered by positive experience. [14] Engaging participants in activities is also enhanced by the small size of the workshop, having a facilitator, and by the experience of return participants.

This objective will be evaluated through end-of-workshop evaluations, subsequent virtual check-ins, and incorporation into educational and outreach innovations of process and participation skills experienced during the workshop.

Objective 4. Repeatable, evolving workshops

To provide a workshop model that can be repeated, evolve in response to evaluations, and adapted by participants.

Background and rationale to objective 4

If workshop costs are kept low and logistics simple, then further workshops can be arranged without organizer burnout, which might encourage participants to arrange their own workshops along similar lines. Moreover, if such workshops develop a reputation of being generative and restorative, enough people will apply without expecting full underwriting of expenses or honoraria, thus keeping costs down. With repeated workshops lessons learned from workshop evaluations can be addressed by the organizer, advisory group, facilitator, and participants in subsequent workshops, which is rarely the case when evaluations are made for once-off workshops.

Achieving and evaluating objective 4

a. The workshop budget and participants' expenses will be kept low by participants sharing expenses for meals and by holding the workshop close to airports served by low or moderate cost national and international flights (Boston and Providence).

b. The evaluations described under the four project objectives address four potential audiences and goals:

i. Workshop organizer and advisory group-to guide them in continuing to develop the workshop in this and future workshops

ii. Potential future participants-to guide them in choosing to participate, and knowing what to expect

ii. Current participants-to allow them to take stock of how to get the most from this workshop and others in the future

iv. External colleagues and funders-to make decisions about support to give to proposals for future workshops.

c. By posting evaluations and testimonials on a workshop website under the NewSSC umbrella, the experience of the workshops can be cumulative. Prospective participants and proposal reviewers can appreciate the style and substance of the workshops, given that they depart from the familiar format of a tight schedule of sessions established in advance. [15]

d. The long-term impact and replication of the workshop model may be hinted at in the participants' evaluations and educational/outreach innovations, but cannot be firmly established during the time period of any workshop and its six-month follow-up.

5. Tangible outcomes and experiences developed beyond the workshop [added June 2011]

For participants to go on to build on the tools and processes of the workshop, on connections made among participants, and on their contributions to the issue at hand, buoyed by the enthusiasm, hope, resolve, and courage that is generated by the learning, interacting, sharing, connecting, and communing that happens during the workshop.

Background and rationale to objective 5

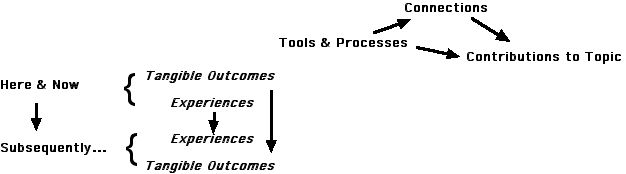

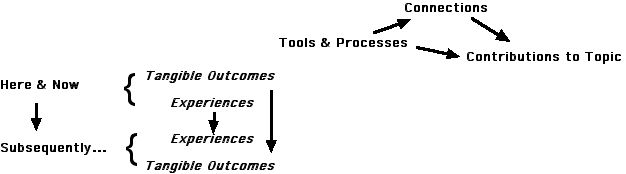

A new schema for what goes on in NewSSC workshops revolves around three contrasts or movements: Here & now vs. Subsequently; Tangible outcomes versus Experiential; and Process as Product (Tools & Processes and Connections) versus conventional Products (Contributions to the Topic).

The fifth objective aligns the schema with the first 4 objectives, which have been stated since the early days of NewSSC.

AAAS (1997). Blueprints for Reform. . http://www.project2061.org/publications/bfr/online/blpintro.htm.

Boyer, E. (1990). Scholarship Reconsidered: Priorities of the Professoriate. Princeton, N.J, Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

Doran, K. and J. Garrett 2005. "Freaks (seminar syllabus)," http://academics.hamilton.edu/courses/ soph222/ (viewed 11 Aug. 05)

Elbow, P. (1981). Writing with Power. New York, Oxford University Press.

Fausto-Sterling, A. (2000). Sexing the Body: Gender, Politics and the Construction of Sexuality. New York, Basic Books.

Gross, P. R. and N. Levitt (1994). Higher Superstition : the Academic Left and its Quarrels with Science. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Gilbert, S. F. (1997). "Bodies of Knowledge: Biology and the Intercultural University," in P. J. Taylor, S. E. Halfon and P. E. Edwards (Eds.), Changing Life: Genomes-Ecologies-Bodies-Commodities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 36-55.

Gilbert, S. F., A. L. Tyler, et al. (2005). Bioethics And the New Embryology: Springboards for Debate. Sunderland, MA, Sinauer.

Hagen, J., D. Allchin and F. Singer (1996). Doing Biology. New York: Harper Collins.

Jungck, J. (Ed.) (1997). The BioQUEST Library, Volume IV. New York: Academic Press. (See also http://bioquest.org)

Martin, B. and E. Richards (1994). Scientific knowledge, controversy, and public decision making. Handbook of Science and Technology Studies. S. Jasanoff, G. Markel, J. Peterson and T. Pinch. Berverly Hills, Sage: 506-526.

McNeal, A. P. and C. D'Avanzo (Eds.) (1997). Student-active Science: Models of Innovation in College Science Teaching. Philadelphia: Saunders College Publishing.

Montgomery, S. L. (1994). Minds for the Making: The Role of Science in American Education, 1750-1990. New York: Guilford Press.

Parens, E. (2004). "Genetic differences and human identities: On why talking about behavioral genetics is important and difficult." Hastings Center Report (January-February): S1-S36.

Paul, D. (1995) Controlling human heredity, 1865 to the present. Atlantic Highlands, N.J.: Humanities Press.

-------(1997) "The history of newborn phenylketonuria screening in the U.S.," Appendix 5 in N. A. Holtzman and M. S. Watson (Eds.), Promoting Safe and Effective Genetic Testing in the United States. Washington, DC: NIH-DOE Working Group on the Ethical, Legal, and Social Implications of Human Genome Research, 137-159. biotech.law.lsu.edu/research/fed/ tfgt/appendix5.htm

Taylor, P. (1997) "Teaching Philosophy," http://www.faculty.umb.edu/peter_taylor/ goalsoverview.html

--------(1998) "Natural Selection: A heavy hand in biological and social thought," Science as Culture, 7 (1), 5-32.

-------- (2000a). "Conditions for a Successful workshop," http://www.faculty.umb.edu/pjt/ECOS.html#appendix (viewed 15 Aug. 05)

-------- (2000b). "Generating environmental knowledge and inquiry through workshop processes," http://www.faculty.umb.edu/pjt/ECOS.html (viewed 15 Aug. 05)

--------(2003) "Non-standard lessons from the "tragedy of the commons"," in M. Maniates (Ed.), Encountering Global Environmental Politics: Teaching, Learning, and Empowering Knowledge. Boulder, CO: Rowman & Littlefield, 87-105.

Notes

Related Workshops and Seminars at UMass Boston

"Changing Life Working Group" -- monthly meetings in Spring 1999 allowing participants "to share insights, experience, experiments, struggles, and plans about influencing science and environmental education, popularization, and citizen activism." This initiative evolved in a series of summer workshops.

"Science-In-Society, Society-In-Science" -- a one-day event in July 1999 (see evaluation )

"New Directions in Science Education and Society" -- three 2-day workshops offered through UMB Continuing Education in July 2000

"Helping each other to foster critical thinking about biology and society" and "...about environment, science, and society" -- intensive weekend workshops for college-level educators in July 2000 and 2001, respectively

Pre-conference workshop on "Teaching History, Philosophy, and Social Studies of Biology" before the July 2001 meetings of the International Society for History, Philosophy, and Social Studies of Biology.

Education for Sustainability Curriculum development workshops at UMB, Spring 2003

Inter-college Faculty Seminar in Humanities and Science at UMB

Spring 2004, 2005

[1] See example from 2005 workshop, www.stv.umb.edu/orsseo1.doc, which involves students comparing three accounts of a new finding in genetics.

[2] As reported by a participant at the 2004 and '05 workshops: "At the Center for Social Studies of the University of Coimbra, in Portugal, Jočo Arriscado Nunes and Marisa Matias have been working on the further development and use of some of the methods of participatory engagement that have been part of the NewSSC toolkit, such as different versions of mapping workshops, as well as other approaches which may be explored, such as different forms of hybrid fora and participatory theatre. These have been used as resources for collaborative production of knowledge about complex processes in situations related to public health, environmental problems, legal procedures and access to justice, political and ethical issues related to human reproduction and experimentation with animals, among others. This has taken the form of training courses for academic and non-academic publics (including, among others, activists, officials of public institutions and local government, civil protection agents and researchers in the biological and biomedical sciences). The same resources are being used by graduate students as tools for participatory action research. The overall assessment of these experiments is that these procedures are excellent resources for a pedagogy of complexity and for a pedagogy of engagement."

[3] Although some evaluations of previous workshops conveyed that new projects and classroom activities had been hatched, the submission of educational innovations and outreach activities was not required. The stipend should remind participants of their commitment to work on their own product and to work with others to achieve something that is high quality.

[4] Such pre-posting review of curricula and teaching notes would be similar to the vetting done by the Problem-Based Learning Clearinghouse, https://chico.nss.udel.edu/Pbl/

[5] E.g., "Workshops for participatory restructuring of knowledge-making and social change," my paper in session on ""Representing and engaging with unruly processes" that I have proposed for the 2005 Social Studies of Science meetings.

[6] From evaluations of the 2004 workshop: "The workshop diminished my skepticism and personal reluctance; once here, I participated, and had moments of surprise and recognition that validated these approaches for me." "For me the great strength of the workshop was that it enabled a relaxed mind and therefore playfulness and creativity. It takes some courage to go with this set up because the program is open and the progress develops in the making."

[7] From the draft evaluation of the 2005 workshop: "the participants' described connecting to new and valuable people and ideas, entering new streams of thought, and productively reshaping existing conceptual structures. A shared theme is transforming/transformative relationships with people and ideas. In all cases the participants described processes of connecting with people and/or ideas that would broaden the scope of their thinking. People at very different places in their careers-a graduate student, a scientist moving into science studies, a senior scholar-all saw themselves moving toward new relationships that would inform and, to greater and lesser degrees, transform their work. This suggests that the workshop met the needs of a diverse group of people as each individual created her or his own way to "engage constructively beyond their current disciplinary and academic boundaries.""

[8] www.stv.umb.edu/newssc04eval2.html and www.stv.umb.edu/newssc05eval.html

[9] Steve Fifield, science educator, STS scholar, and program evaluator, U. Delaware (participant-evaluator, NewSSC 2004 & '05 workshops)

Jočo Arriscado Nunes, sociologist of biomedicine, University of Coimbra (participant, NewSSC 2004 & '05 workshops)

Vivette García-Diester, graduate student in philosophy of biology, UNAM, Mexico (participant, NewSSC 2005 workshop and co-organizer of ISHPSSB's 2004 graduate student "Future Directions" conference; www.ishpssb.org/workshop2004/summary.htm)

[10] The experience of previous workshops is that the scientists who chose to attend were enthusiastic participants in such activities-contrary to a comment in a review of a previous proposal, "You cannot waste [scientists'] time with autobiography and freewriting."

[11] From an evaluation of the 2004 workshop: "The pattern of opening up, interconnecting ideas and foreshadowing on the first day proved to be effective" ( www.stv.umb.edu/newssc04eval.html).

[12] E.g., during the Spring 2005 Workshop on "How complexities of the social environment shape the ways that society makes use of knowledge about 'genetic' conditions," participants discussed with Diane Paul her article on the history of PKU screening (Paul 1997), which they had read as homework, and then were led in a teaching activity I have been developing on "diagramming intersecting processes," www.stv.umb.edu/i04IP.doc

[13] From an evaluation of the 2004 workshop: "[P]articipation at this level is exhausting." ( www.stv.umb.edu/ newssc04eval.html). This counters the concern of a reviewer of a previous proposal that such workshops would be "a way for people in the field to... get a few quiet hours away from teaching and other responsibilities to write."

[14] From an evaluation of the 2004 workshop: "Many, many workshops are dysfunctional-this one wasn't."

From a commentary on the 2005 workshop: "I was very interested in participating in the workshop because I wanted to learn how people outside philosophy of science think about areas and aspects of biology on which my philosophical work is focused. The issues I address and the way I address them are largely shaped by my close interaction with philosophers. Although I have gained insights from historical and sociological literature, I have not spent much time discussing general issues about biology with socially oriented sociologists and historians. I felt that I have been using their work for my purposes without having a good understanding of how they might use my work for their purposes. I saw the workshop as an opportunity to learn more about the purposes of those studying science outside the HPS tradition. I hoped to learn that some of my work might be helpful for addressing issues as they are shaped by a variety of intellectual communities.

When workshop participants were asked to bring their favorite poetry and musical instruments and were asked to begin with lengthy biographical introductions, I became concerned: was I embarking on a serious intellectual endeavor or summer camp? It's not that poetry and music are not serious intellectual endeavors, but they are not what my serious intellectual endeavors are about. And I simply don't have the leisure. But I decided to attend anyway. And I'm glad I did. It turned out that the set-up of the workshop helped establish a non-threatening environment where people could immediately get past the defensive posturing of many intellectual endeavors and express what motivated their intellectual interests. And some of the activities themselves, including the biographical introductions and evening readings, helped me understand different kinds of motivations for pursuing an area of science studies. The feature of the workshop that made me suspicious of the endeavor, turned out to facilitate exactly what I wished to gain, intellectually, from the workshop."

[15] See, as examples, the comments quoted in previous footnotes.

Last update 19 June 11